City Stories

City Stories is the media hub for the blogs produced by City of Hope. Collectively, our blogs provide breaking news and rare insights into a range of health-related topics, including new treatments, academic opportunities, patient victories, research breakthroughs, physician profiles, and the impact our donors are making.

Patient Stories

Patient Care & Treatment

Research

Philanthropy

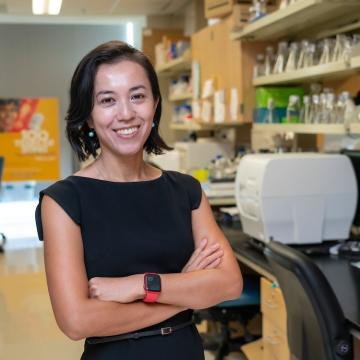

Physician News

Receive Blog Updates

Make sure you get all the latest updates on our scientific breakthroughs, physician news, research developments, patient stories, and more.

Contact Our Newsroom

For breaking health news, interviews, photo requests, visiting or filming at City of Hope, or the most current information and resources available, please contact City of Hope's Media Hotline.