When Brad Berger was a teenager, he’d spend summers helping out in his father’s contracting business, doing plaster work in commercial buildings.

Decades later, he wondered about the heaviness in his chest. Fearing a heart problem, he called his doctor.

Tests did reveal some cardiac issues: a blocked coronary artery (he got a stent) and a worn-out aortic valve (it was replaced).

But one test, a PET scan examining his abdomen, turned up something unexpected.

“I was shocked,” he recalls. “So was my doctor.”

There was a small nodule on Berger’s left lung. A biopsy confirmed the frightening diagnosis.

He had mesothelioma, almost certainly caused by asbestos exposure on a construction site, all those years ago.

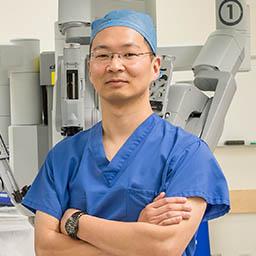

“The typical latency period for mesothelioma is 30 to 50 years,” explained Jae Y. Kim, M.D., City of Hope’s chief of thoracic surgery. “One remodeling job can do it. Or you can get it indirectly, if a parent comes home with asbestos fibers on his clothing and the kids breathe it in.”

Mesothelioma, cancer that develops in the lining surrounding internal organs, usually the lungs (but occasionally the heart, groin or abdomen) is very rare, with only about 3,000 new cases a year in the U.S. It’s deadly. Most patients live just a few months. Less than 8% survive five years. It’s one of the toughest malignancies to treat.

'Relentless and Pernicious'

“It’s relentless,” said Kim, “and quite pernicious. It sneaks up on you, it’s very hard to get rid of, and it keeps coming back. It doesn’t behave like other cancers, and it’s less susceptible to anti-cancer drugs.”

Mesothelioma was virtually unheard of before asbestos became a commonly used industrial material in the 1950s. Since then, 50 countries have banned asbestos, but the U.S. has not. Though tightly regulated, asbestos still turns up in automotive brake pads and gaskets, roofing products and fireproof clothing, a sore point among mesothelioma activists who circulate petitions every September — Sept. 26 is Mesothelioma Awareness Day — to press Congress to banish the substance forever.

After the initial shock wore off, Berger says reality set in. “It was devastating,” he said. “I thought this couldn’t be happening to me. I was scared and confused over what to do next. I asked my doctor about my chances. All he could say was, ‘Miracles can happen.’”

Berger went looking for that miracle, throwing himself into researching and visiting several oncologists and hospitals. Not one to rely strictly on referrals, he cold-called City of Hope. At his first meeting with Kim, he remembers being “impressed with his depth of knowledge and his demeanor.”

It was a good match, probably because that “demeanor” includes a drive to take on tough challenges. Far from being discouraged, Kim says the complexities of mesothelioma are precisely what attract him.

“This disease has a prognosis so poor,” he said, “and we know so little about it, plus there have been so few treatment advances in the last 30 to 40 years, so it seems like an area with a real opportunity for progress.”

Surgery is the primary weapon. Caught early enough, a mesothelioma tumor can be excised by removing the lung lining where it was found. Unfortunately, with that “pernicious” multidecade latency period, many cases of mesothelioma can be quite advanced by the time they’re diagnosed.

Most mesothelioma tumors are made of relatively slow-growing epithelial cells, and surgery works best in those cases. But some tumors — up to 20% — involve so-called sarcomatoid cells, which grow back rapidly after surgery and may even accelerate their growth in response to it.

For those reasons surgery — when it’s done at all — is often followed by weeks of chemo (the drugs of choice are the platinum-based cisplatin, carboplatin and more recently pemetrexed, also called Alimta, approved in 2004) and multiple sessions of radiation.

Key Developments in Treatment

Recent advances have been sparse, but they’re important.

For example, studies have shown that giving chemo before surgery leads to much better results.

“This is now becoming the standard of care,” said Berger’s oncologist Ravi Salgia, M.D., Ph.D., an internationally renowned lung and thoracic cancer expert and the Arthur & Rosie Kaplan Chair in Medical Oncology. “The idea is to reduce the tumor bulk so the surgery is not as complex.”

Bigger breakthroughs may lie with immunotherapy, an area where City of Hope plays an especially significant role.

Researchers are very excited about the “remarkable” phase 2 clinical trial results for durvalumab: When added to standard chemotherapy, survival rates climbed from the typical chemo-only 12 months to more than 20 months.

“This is noteworthy for its potential,” explained Kim, “because we already know durvalumab works well on other cancers, and it’s well tolerated.”

Perhaps even more significant is the June 2020 Food and Drug Administration approval of Keytruda for inoperable and metastatic tumors in many cancers including mesothelioma, thanks in large part to clinical trial work done at City of Hope.

The Keytruda trial focused on biomarkers common to many cancers, rather than on any one form of the disease. This approach may ultimately help uncover new drugs for mesothelioma more rapidly than the current method of trying to create, recruit and run single, specific trials for such a rare illness.

“I believe the FDA made the right decision,” said principal investigator Marwan G. Fakih, M.D., the Judy & Bernard Briskin Distinguished Director of Clinical Research. “However, much still needs to be learned.”

It would be hard to use the word “lucky” when talking about anyone with mesothelioma, but in Berger’s case, the term may apply. Thanks to that PET scan (which was looking for something else), doctors did catch his tumor very early. Berger recalls Kim exclaiming, “This is the smallest mesothelioma tumor we’ve ever seen!” Furthermore, it was situated in an easily reachable spot on the outer part of the lung lining.

Even circumstances broke his way. Because of his various cardiac issues, Berger had to wait and recover for a while before he could have surgery. Taking advantage of that extra time, Salgia started Berger on chemotherapy as well as the immunotherapy drug atezolizumab, which turned out to make a profound difference: When the surgery finally took place there was very little cancer left, and none of it was active. Lucky indeed.

Berger is now getting radiation treatments — he’ll need 30 in all — and he’s doing very well. He’s glad he made that cold call.

“City of Hope has more than lived up to its substantial reputation,” he said. “I have been to countless appointments and procedures and have been treated with respect and dignity. The folks that work at City of Hope are wonderful … and I have been lucky to have been cared for by many of them … to receive their healing help.”