Steven Smith, Ph.D.

The working hypothesis in my laboratory is that genomes, like other components of living things are the subject to evolution by natural selection. This line of investigation is a tradition at City of Hope that was founded by Susumu Ohno. My laboratory has explored aspects of genome evolution linked to epigenetics. In particular, work in the lab has begun to unravel the roles of non-B structures in the spontaneous epigenetic and genetic damage that underlies both tumorigenesis and cellular ageing.

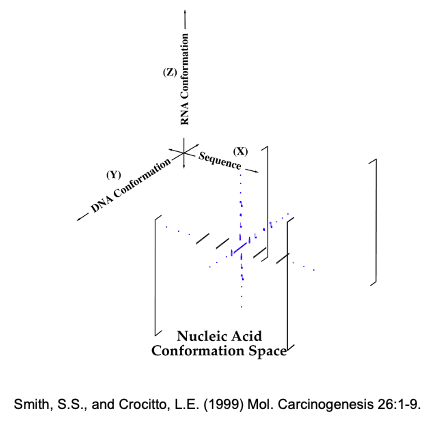

Figure 1: Nucleic Acid Conformation Space. Most DNA sequences in the genome adopt a Watson-Crick B-DNA conformation (Dark sequences along the X-axis). However, certain sequences (Blue sequence Y-axis) have the potential to adopt a various non-B folded structures when they are in a single-stranded state during replication and transcription, with the two complementary strands possessing different potentials. Finally, RNAs copied from these DNA sequences also have the potential to adopt unusual structures (Z-Axis).

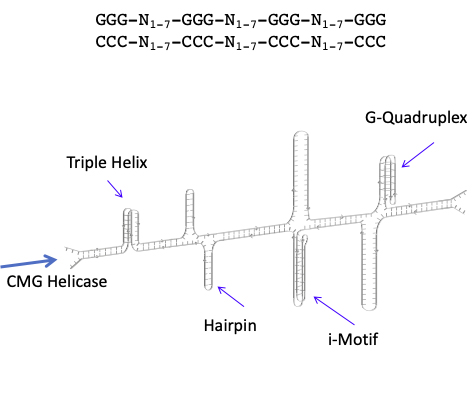

Biologically, it is useful to consider the influence of nucleic acid conformation space (Figure 1) on genome evolution. Genetic functionality requires classical B-DNA for somatic inheritance. It also requires that non-B structures be suppressed when DNA sequences are copied, and may require the capacity to elicit their formation if they play a role in epigenetics. This later process, i.e. the orchestrated formation of non-B structures in gene expression and RNA processing are hotly debated topics, with structures like the G-quadruplex, i-motif and triple-helix (Figure 2) all implicated in possible epigenetic roles.

Figure 2: Structures associated with the sequence GGG-N1-7-GGG-N1-7-GGG-N1-7-GGG. Replication through these sequences is preceded by CMG helicase action.

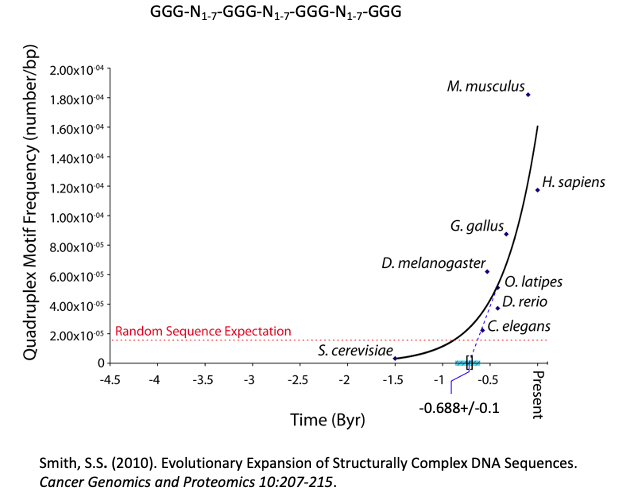

The advent of sequences capable of formation of these canonical structures and the intermediates that form them in DNA genomes appears to have taken place rather late in biological evolution, with biota from the Ediacaran epoch [635-541 million years before present] likely to be the first organisms capable of tolerating them. That the increasing frequency of these sequences tracks the evolution of biological complexity in the animal kingdom strongly suggests an epigenetic role for them (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The frequency of GGG-N1-7-GGG-N1-7-GGG-N1-7-GGG Sequences Increases with Organism Complexity in the Animal Kingdom. This indicates that the sequences are under positive selection and may play a role in epigenetics. Extrapolation of the graph to the time axis suggest an origin near the beginning of the Edicaran Epoch.

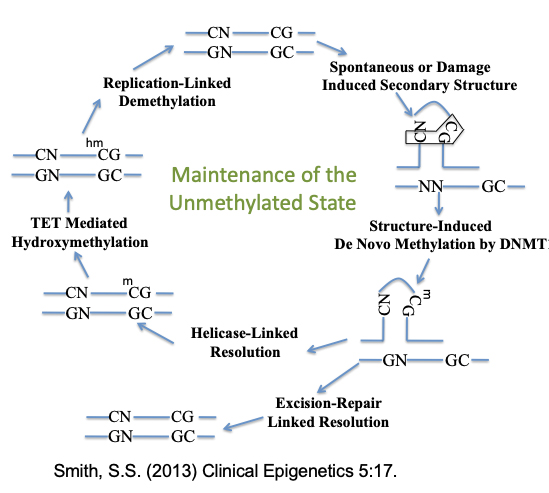

On the other hand, among the most complex organisms, loss of control of the formation of these sequences can have a variety of effects like epimutations through the disruption of DNA

Figure 4: Maintenance of the Unmethylated State. DNA methyltransferases are known to selectively methylate non-B structures where they stall and remain tightly bound resulting in hypermethylation at non-B sites and hypomethylation elsewhere. Maintaining stasis in somatic methylation patterns requires Helicase linked resolution of the non-B structures and/or Excision Repair linked removal of bound methyltransferase followed by Tet mediated demethylation. Ref 1 and Ref 2.

methylation patterns seen in cancer (Figure 4), and mutations like the deletion mutations present in cancer cells at sites of i-motif formation (Figure 5).

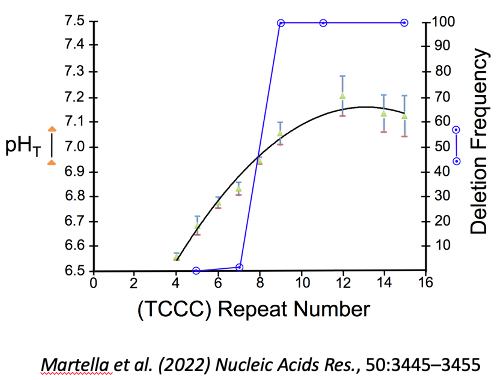

Figure 5: Length dependence of i-motif formation at neutral pH correlated with deletion frequency. The i-motif structures formed by (TCCC)n form at neutral pH (indicated by a pHT value of 7.0 to 7.3) only when the number of repeats (n) exceeds 8. Sequences at various locations in the human genome show deletions only where the number of repeat elements exceeds 8 permitting the i-motif to from.

pHT value: closed triangles (green) ± standard deviation determined from the titration curve fit. Fraction of cloned sequences with a deletion: open circles (blue).

Current work suggests that this loss of control may be progressive in somatic lineages thereby contributing to both carcinogenesis and aging.

Professor Smith’s publications can be viewed at Research gate.

Biomedical Reseach Center

1500 East Duarte Road

Duarte, CA 91010

Duarte Cancer Center

Duarte, CA 91010

1974, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, Ph.D., Molecular Biology

1968, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, B.S., Zoology

2022 - present. Professor Emeritus, Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, City of Hope, Monrovia, CA

2016 - 2022 Professor Emeritus, Department of Department of Hematologic Malignancies Translational Science, City of Hope, Monrovia, CA

2001 - 2016, Professor of Molecular Science, Division of Urology/Department of Surgery, City of Hope, Duarte, CA

1990 - 2001, Director, Department of Cell & Tumor Biology, Division of Surgery, City of Hope, Duarte, CA

1990 - 1998 Director, Program in Molecular Carcinogenesis, NCI-designated Clinical Cancer Center, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA

1995-2000 Research Scientist, Division of Surgery, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA

1987 - 1995, Associate Research Scientist, Division of Surgery, City of Hope, Duarte, CA

1985 - 1987, Assistant Research Scientist, Department of Thoracic Surgery, Division of Surgery, City of Hope, Duarte CA

1982 - 1984, Assistant Research Scientist, Department of Molecular Biology, City of Hope, Duarte, CA