As tens of thousands of new COVID-19 cases crop up each day worldwide and measures to slow its spread disrupt everyday life, the hopes of billions hinge on the creation of a vaccine.

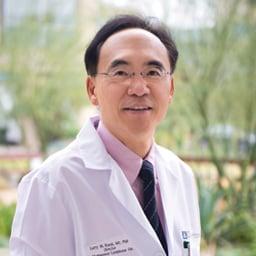

City of Hope scientists are helping drive that effort, including a research group led by Larry W. Kwak, M.D., Ph.D., deputy director of City of Hope’s comprehensive cancer center and the Dr. Michael Friedman Professor in Translational Medicine.

“We have a vested interest in preventing COVID-19 because most, if not all, of our patients are immunosuppressed and therefore, extremely vulnerable to this infection,” he said. “It touches directly on our mission of curing cancer.”

His coronavirus work builds on a vaccine he pioneered for the treatment of lymphoma. That basis is expected to cut a faster path to clinical trials if his team’s efforts against the coronavirus find success.

“What gives us a speed advantage is that the basic delivery platform has already been allowed by the FDA,” said Kwak, who also is director of the Toni Stephenson Lymphoma Center within the Hematologic Malignancies and Stem Cell Transplantation Institute at City of Hope. “We’ll probably save about a year because we have the clinical vector in hand.”

Tapping the source code

Kwak’s prospective COVID-19 vaccine will work like many others, by introducing elements of an infectious microbe to a person’s system so that the body’s natural defenses can recognize and destroy the invader. In this case, his technology deploys “naked DNA” — the source code of life — to fight disease.

His team will fuse genetic material that encodes proteins from the coronavirus with a sequence that encodes a type of immune molecule called a chemokine. The small proteins in this family serve to attract immune cells, mustering them to the site of infection, for instance. The engineered hybrid DNA would be delivered with an injection under the skin.

This approach is expected to impart a pair of key advantages: speed of development and safety of delivery.

The payload for Kwak’s platform will rely upon the latest information from other research groups that are unraveling the genetic code of the coronavirus, as well as its mutated variations. Any lab looking to produce a vaccine would need to screen many coronavirus protein candidates in preclinical studies, searching for the most effective version. For Kwak’s team, switching out genetic sequences at this stage can be accomplished swiftly.

“This is high-throughput,” Kwak said. “Because it’s naked DNA, we can manipulate it very quickly to come up with the best candidate.”

At the same time, some other preventive strategies introduce a health risk. Vaccines that carry a weakened version of the targeted microbe can backfire if the pathogen proves stronger than thought and instead causes the infection the vaccine is designed to prevent. Not so with Kwak’s platform.

“We’re talking about a more sophisticated approach, where we use genetic sequences rather than the virus itself,” he said. “These genetic sequences are not capable of causing the actual infection.”

Reasons for optimism

The DNA-based delivery system is adapted from a personalized therapeutic vaccine for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma that Kwak developed. A recently completed first-in-human safety trial of this treatment demonstrated favorable findings. In patients diagnosed with a rare subtype called Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, the lymphoma vaccine displayed no serious toxicity and even showed changes to the tumors’ local environment, suggesting that the therapy works.

More than that, the coronavirus isn’t the first virus that Kwak has targeted with his DNA platform. In recent years, his lab has developed an HIV vaccine using the same technology, and investigations with laboratory models showed early promise.

As a physician-scientist, Kwak is particularly well-positioned to take a potential medical breakthrough from the laboratory bench to the patient’s bedside. His acumen for translational research has been recognized again and again, including his spot on TIME magazine’s 2010 list of the most influential people in the world.

City of Hope, with its mission of turning science into practical benefit, has cultivated expertise and infrastructure that may help advance Kwak’s investigations.

For decades, virology experts on campus have tackled diseases such as HIV/AIDS and cytomegalovirus, which can be a deadly threat to immunocompromised patients recovering from blood stem cell transplants.

Additionally, certain therapies under development at City of Hope rely on weaponizing neutered viruses against cancer.

City of Hope also runs three on-site facilities dedicated to manufacturing investigational therapies for clinical trials. This allows researchers to skip the potentially time-consuming step of finding outside partners to make such treatments.

The Center for Biomedicine & Genetics at City of Hope, a resource for manufacturing biological therapies, could provide that very same boost as Kwak moves his COVID-19 vaccine forward.

“These manufacturing capabilities make us different from most academic medical centers,” he said. “If it’s faster, we’ll just do it ourselves.”